As the clock struck midnight on August 15, 1947, India awoke to freedom, but also to fire, blood, and exile. Freedom at Midnight delivers a heart-wrenching yet inspiring account of the subcontinent’s partition, revealing how vision, vanity, and violence shaped a new world order. Through intimate portraits of Gandhi, Nehru, Jinnah, and Mountbatten, this classic illuminates the high cost of liberty and the enduring power of human decency. A must-read for leaders, historians, and seekers of truth. Summary powered by VariableTribe.

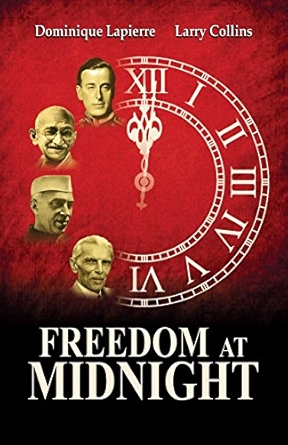

Freedom at Midnight stands as one of the most compelling and meticulously detailed historical narratives of the twentieth century, offering an immersive chronicle of the final year of British rule in India and the harrowing birth of two sovereign nations, India and Pakistan. Penned by the celebrated journalistic duo Dominique Lapierre and Larry Collins, this landmark work transcends conventional historiography by blending rigorous research with the pacing and emotional depth of a literary epic. The narrative begins in March 1947, when Lord Louis Mountbatten, the great-grandson of Queen Victoria and a decorated Royal Navy officer, arrives in New Delhi as the last Viceroy of India. His mission, assigned by Prime Minister Clement Attlee, is deceptively simple on paper: oversee Britain’s orderly withdrawal from its most prized colony within a matter of months. Yet what unfolds over the next eighteen weeks is anything but orderly, it is a maelstrom of political brinkmanship, communal bloodshed, visionary idealism, and human tragedy on a scale rarely witnessed in modern history.

At the core of this drama are three colossal figures whose ideologies, personalities, and decisions would shape the destiny of over 400 million people. Mahatma Gandhi, the frail yet indomitable “Mahatma” (Great Soul), embodies the moral conscience of the independence movement. Clad in hand-spun khadi and armed only with truth and nonviolence, he envisions a united India where Hindus, Muslims, Sikhs, and others live as brothers under a shared sky. Jawaharlal Nehru, aristocratic, intellectual, and fiercely secular, represents the future-facing, modernist wing of the Indian National Congress. He dreams of a democratic, industrialized republic rooted in scientific temper and social justice. In stark contrast stands Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the austere and uncompromising leader of the All-India Muslim League. Once a proponent of Hindu-Muslim unity, Jinnah becomes convinced that coexistence is no longer viable and demands a separate homeland, Pakistan, for India’s Muslim minority, whom he believes face cultural and political extinction in a Hindu-majority state.

Mountbatten, charismatic, energetic, and well-meaning, enters this volatile triangle with optimism and a firm deadline: August 15, 1947. But his haste, driven more by British domestic politics and imperial fatigue than by ground realities, proves catastrophic. The authors argue persuasively that partition was not an inevitable outcome but the result of a cascade of misjudgments, missed opportunities for compromise, and escalating fear-mongering by communal extremists on all sides. The decision to divide Punjab and Bengal along religious lines, without adequate planning for population transfers or security, ignites a firestorm. What follows is the largest mass migration in human history: an estimated 15 million people uprooted, over one million dead, and countless women abducted, raped, or killed in the name of honor. Trains arrive at stations filled not with passengers but with corpses; villages are reduced to ash; families vanish overnight.

Yet Freedom at Midnight is not merely a catalog of horrors. It is also a testament to extraordinary courage and compassion. The authors weave in countless vignettes of ordinary heroism: a Sikh farmer shielding his Muslim neighbors from a mob; a British district officer risking his life to escort refugees; a Hindu doctor treating wounded Muslims despite threats to his own family. Most poignantly, Gandhi’s final year becomes a spiritual crusade against hatred. At age 77, weakened by repeated fasts, he travels to the riot-torn heartlands of Bengal and Bihar, using his own body as a moral lever to shame communities into peace. His 73-hour fast in Calcutta in September 1947, a city known for its volatility, miraculously halts the violence, if only temporarily. This act of radical empathy underscores the book’s central thesis: true freedom is not just political sovereignty but the liberation of the human heart from fear and prejudice.

The assassination of Gandhi on January 30, 1948, by a Hindu nationalist who saw him as too accommodating to Muslims, serves as the book’s tragic denouement. It is a stark reminder that the ideals of unity and tolerance remain perpetually vulnerable. Lapierre and Collins do not offer easy resolutions. Instead, they invite readers to sit with the complexity, the brilliance and blindness, the nobility and naivety, of those who shaped this epoch. For contemporary audiences, the relevance is profound. In an age of resurgent nationalism, digital echo chambers, and identity-based polarization, Freedom at Midnight functions as both a warning and a guide. It illustrates how quickly societal fabric can tear when leaders prioritize power over principle, and how resilient it can be when individuals choose empathy over enmity.

More than a historical account, this book is a masterclass in ethical leadership, crisis management, and the psychology of collective trauma. It reveals that nation-building is not a technical exercise but a deeply human one, fraught with emotion, memory, and moral ambiguity. Whether read as a cautionary tale about the perils of rushed decolonization or as an inspirational portrait of nonviolent resistance, Freedom at Midnight endures because it speaks to universal struggles: How do we share space with those who are different? How do we build peace after betrayal? And what does it truly mean to be free?

Summary powered by VariableTribe, this narrative remains an indispensable resource for students of history, practitioners of leadership, and anyone seeking to understand the fragile architecture of peace in divided societies.

The book’s structure mirrors the accelerating tempo of 1947 itself. The opening chapters establish the political deadlock: the Cabinet Mission Plan’s failure, the Muslim League’s Direct Action Day, and the collapse of trust between Congress and the League. Mountbatten’s arrival introduces a note of optimism, but his reliance on charm over strategy soon falters. The middle third plunges into the mechanics of partition, Radcliffe’s secret boundary commissions, the division of assets, the paralysis of civil services. Here, the authors excel in showing how bureaucratic decisions translated into human catastrophe.

The core philosophy of Freedom at Midnight is that history is not driven solely by grand ideologies but by individual choices made under pressure. Gandhi’s choice to fast rather than condemn; Nehru’s choice to embrace secularism despite personal grief; Mountbatten’s choice to prioritize speed over stability, each ripples outward with life-or-death consequences. The principle that emerges is this: ethical clarity in leadership is not a luxury but a necessity during existential transitions.

Real-world applications are manifold. In corporate mergers, leaders can learn from the dangers of poor communication and unrealistic timelines. In community mediation, Gandhi’s methods offer a blueprint for de-escalation through vulnerability. On a geopolitical scale, the book warns against redrawing borders without addressing underlying social fractures, a lesson relevant to conflicts from the Balkans to the Middle East.

Critically, while some historians have questioned the dramatization of certain dialogues, the factual backbone of the book remains robust. Lapierre and Collins conducted over 1,000 interviews, including with Mountbatten himself, and accessed private letters and diaries unavailable to earlier scholars. Their achievement lies in making archival material breathe with urgency and emotion. The book’s enduring power stems from its refusal to reduce history to heroes and villains; instead, it presents flawed humans navigating an impossible situation with varying degrees of grace.